São Savério / Conjunto Habitacional Jardim Celeste, Sacomã district, Ipiranga Sub prefecture

Dona Sofia is 53 years old, single, black, works as a cleaning assistant. From Bahia, she has lived in the community for 10 years, where she bought a shack to get out of the rent. She lives with 4 people. Every day she wakes up at dawn to fetch water from the taps in the alleys, because her water tank is always empty, the water never comes to fill it. It has a shower, but it takes a bath with a bucket and a mug, because there’s never enough water.

“There is a tap, no water.”

“There was not a day without going to work because of that [lack of water], because we decided to get water from the bucket at dawn and put it inside the house. Because we can’t stop working. ”

“I don’t run out of water at home because I carried a bucket to fill, wash things, bathe the children.”

Dona Julia, single, black, 30 years old, mother of two children, one being 5 months old. Born in São Paulo, she moved to the community 15 years ago, when she lost her shack in a fire. She is autonomous and is still recovering from the birth of her daughter. Receives assistance from Bolsa Família. She has no water tank and, when the water is lacking, she searches the street tap or counts on the help of her family and neighbors to bathe. Usually, the water arrives at night and has not been lacking as much as in the past. Buy bottled water for the kids and drink tap water. She keeps rainwater in gallons. She would like to pay for the water bill to have water at home, just as it has electricity.

Dona Ana, single, from Bahia, black, 40 years old, lives with her daughter in the community. Today, she is unemployed and receives emergency aid. She moved to the community in 2003, after receiving compensation for being fired from a store when she was pregnant. With the money she bought the shack and left the rent. The shack already had a clandestine connection with the Sabesp network. The house has a 500 liter water tank and Ana does not store water in other ways. But, there is no water constantly and often borrows water from others.

“So the people who already lived here had clandestine connections. And these connections still exist today and people use it, but the structure is too small for many people, the structure is very precarious. ”

“Here in the community we have a large list of demands and we always discuss the lack of water and also the values of the bills that are very high, not only water, but also electricity and we charge for the basic sanitation campaign, ( …) the vast majority of sewers are in the open and this harms not only the population, but the children who live in this community because it facilitates contamination and bacterias that can produce diseases, not only for humans but also for animals. “

Leadership, Dona Antonia, a 56-year-old black woman, lawyer and educator, has participated in housing movements for over 30 years. She moved to the community when she participated in the construction of a collective effort in 1995. She participated in the purchase of a pipeline to guarantee the water supply for the neighborhood. For her, the neighborhood has infrastructure and water supply. Most houses have a water tank. The biggest problem is the residents’ difficulty in paying the water bills. During the pandemic, many stopped paying and, despite negotiations with Sabesp, the supply system was suspended. There were no actions by Sabesp or the City Hall to guarantee access to water for all.

Jardim São Savério is a community that was transformed in 1990 with the construction of a self-managed joint effort of a housing complex for 501 families, in addition to the self-construction of several houses. Today, according to the interviewees, the Conjunto Jardim Celeste has about 1,153 units (652 apartments and 501 houses) and around 5,000 people. In the 3 neighborhoods (Jardim São Savério, Parque Bristol and Vila Liviero) there are at least 20 slums that continue to expand. In total, around 20 thousand people live in the neighborhood.

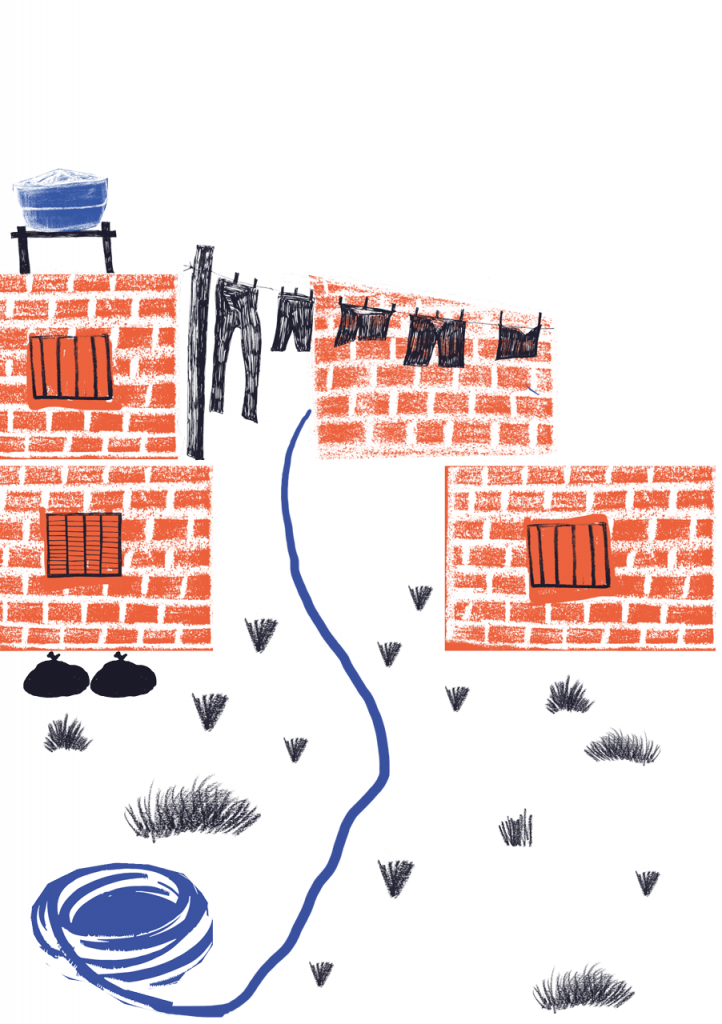

The infrastructure for water supply and sewage collection is present in the neighborhood sector where the state housing is located. Part of this infrastructure was financed by the residents at the beginning of the construction of the first complexes as the acquisition of the pipeline, however, the favelas no longer have this infrastructure and their access to water and sewage collection is through an informal network and at a very low frequency. Both pipes and buckets are used to bring water into the house. There are water tanks, but most of the time they are empty. There is a shower, sink and toilet in the house, but people shower only when there is water.

To guarantee water at home, residents combine a series of strategies such as borrowing water, bathing and washing clothes at neighbors ‘and relatives’ houses, fetching water from the taps in the alleys. Finally, they store rainwater in gallons, buy bottled water to drink, mainly for children and choose the time to wash clothes according to the availability of the water and how much people are using it.

The main problems in the neighborhood today are the difficulty of paying water bills for those who have water supply at home, while for those who live in the favelas the biggest problem is the low water available and its intermittence, to the point where the water tank does not solve the problem.

Photo by: Marilene Ribeiro de Souza e Sheila Cristiane Santos Nobre